China has become one of the music industry’s most talked-about emerging markets — and for good reason.

The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) recently reported a 35% increase in profits from the nation’s recorded music sector just in the last year. A handful of household international artists like Steve Aoki are already making the majority of their cash in China. With a huge population and twice as many smartphone users as people in the States, China’s swelling demand for music and entertainment seems like a no brainer.

However, for musicians looking to make their mark in the Middle Kingdom, promoting music and touring in China is anything but.

Photo by Catherine Lee

China’s music landscape differs from the rest of the world more so than any other country, and a brief look at its musical history may just reveal why.

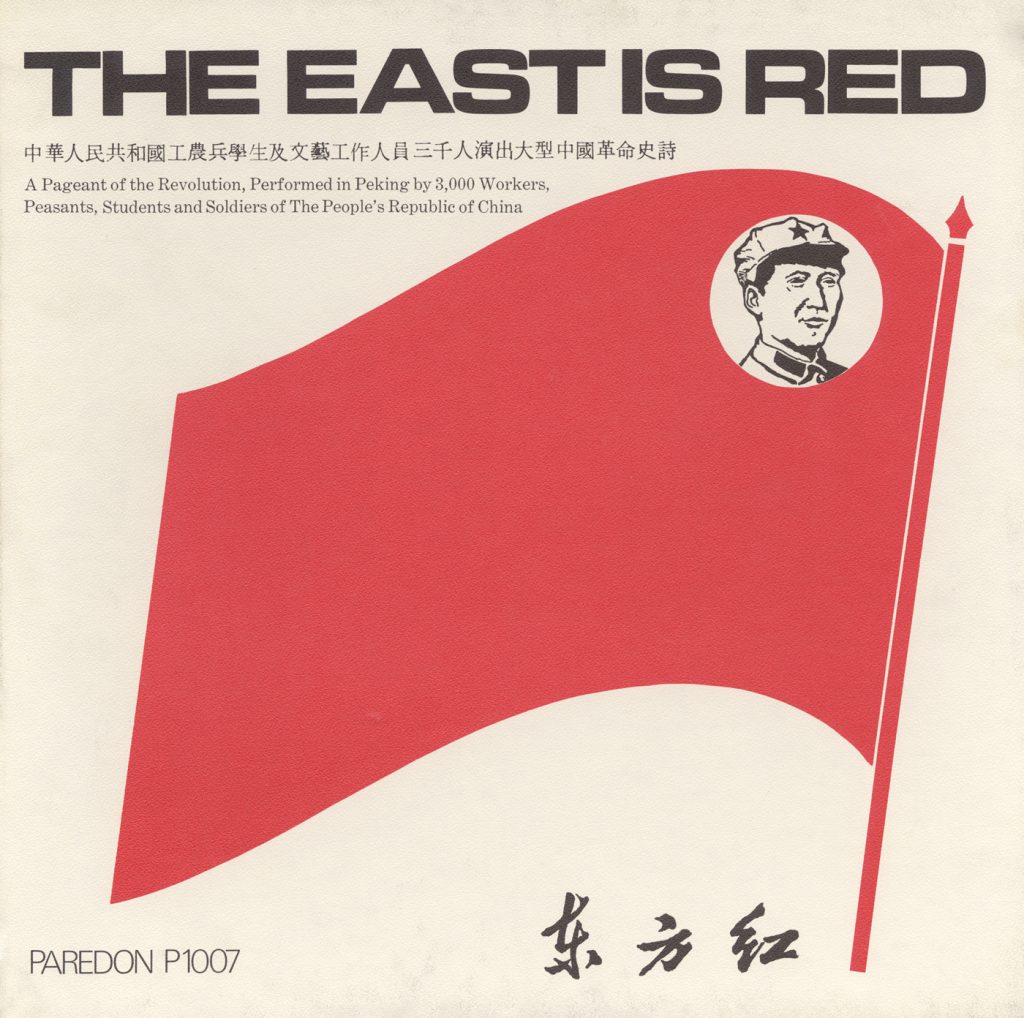

In 1949, Mao Zedong came to power and founded the People’s Republic of China, the single-party state controlled by the Communist Party of China, which is still in power today. During this time, Mao harnessed music as a mass media vehicle to implement his dramatic ideological changes across a nation in turmoil, resulting in genres like Patriotic Music (爱国歌曲) and Revolutionary Music (革命歌曲).

Many point to this as the birth of popular music in China, even though music distribution and content were agenda-driven and tightly controlled by the government. Even after the height of political music during the Cultural Revolution, the “popular music” that followed saw limited invention beyond nationalist messages or conservative love ballads. Music’s role in society and peoples’ fear of persecution were decades engrained, and the importation of Western music, often politically charged, was tightly controlled or forbidden altogether.

Then came the 80’s and 90’s.

Western music gradually crept into China by way of Dakou (打口), which were millions of unsold Western records and cassette tapes imported for disposal. They were sawed or cut as trash, but unbeknownst to the government, many were still circulated and treasured amongst Chinese youth hearing something new for the first time. It was not until Wham!’s 1985 performance at the People’s Gymnasium in Beijing that the Chinese government would reluctantly hold its first-ever Western pop concert.

Since then, many more overseas artists have played China, and each has been subject to the government’s review and approval.

东方红 “The East is Red”

Smithsonian Folkways

打口 dakou tapes with slashes

Radii China

Though the world’s popular music today may feel less politically charged than the past, understanding the historical context of music as a political vehicle in China helps to explain the country’s conservative approach. In the West, people endowed music with the power to be political, whereas in China, the government did.

Music has long been viewed as a means to move the masses and with that power, comes a responsibility to protect it.

1985 Wham! concert in China

Before an artist steps on stage, they must undergo a long and rigorous review process.

Immediate no-gos include critiques of the Chinese government or its territories and overt references to drugs, sex, or violence. One popular reason for rejection in the past has been vocalizing support of Tibetan independence or the Dalai Lama, which has kept China’s doors closed to the likes of Lady Gaga, Maroon 5, U2, Bon Jovi, and Oasis (who were famously rejected after the government discovered a band member’s participation in a small Tibet benefit concert ten years before).

In 2017, the Ministry of Culture squashed a Justin Bieber concert on the grounds of “bad behavior,” following his recent arrest for drunk driving, berating a portrait of former U.S. president Bill Clinton, and accounts of public urination. In 2018 citing similar “bad behavior,” China banned hip hop music and tattoos from national TV entirely. While artists aligned with either are often looked upon with greater scrutiny, enforcement of the ban has been inconsistent, and since then, many rappers such as Smokepurpp, Joey Bada$$, and Rae Sremmurd have played China scot-free.

Even if content censorship was straightforward, other requirements for a performance visa are ever-changing and may differ depending on the region, the artist’s country of origin, or even superfluous factors like time of year, current events, or other concerts happening at the same time. Working with a seasoned and reliable promoter or representative is a must for navigating the process, which is referred to as baopi (报批), meaning “report for approval.”

It’s typical for a festival promoter seeking to obtain an event permit to ask an independent American artist on the bill to provide:

- Setlist and .mp3 files (exactly as they will be performed on stage)

- Transcripts of all lyrics (including Mandarin language translations)

- Live performance video footage for each song

- 3 music videos

- Biography (translated)

- Show/tour history for the last 2 years

After this information is sent to the Ministry of Culture, the government reviews and conducts its own additional research. This process can take anywhere from a few weeks to several months, and filing fees are not refundable for rejected applications. Artists and promoters must wait until approval is granted before announcing and promoting shows, which can sometimes fall within days of the performance.

The process, which seemed to only apply to large-scale performances, has been recently enforced on club and live-house shows with as little as 300 attendees. This can be a huge financial burden for independent artists or small-time promoters who face similar application fees but much smaller profit margins.

As recent as spring of 2019, an independent American artist playing 300-700 capacity rooms across China was asked to pay as much as 8,000 RMB (~$1,200 USD) in baopi fees for one show in a 500 capacity room in Beijing. Even with a sold-out show, earnings wouldn’t have been enough to cover application fees, let alone the promoter’s basic expenses. While many artists and promoters of smaller shows skip this process entirely, it’s becoming a risk that fewer are willing to take.

For Ross Miles, a Shanghai-based artist manager and booking agent at Scorched Asia, China’s complex artist performance permitting and visa process can feel like a “total disconnect between real life and policy.”

Scorched has a reputation for consistently doing business above the board, handling China booking for Princess Nokia, Mitski, and others. They’re also behind Concrete and Grass, an annual three-day festival with genre-crossing billing that has included everyone from Chinese pop superstars such as Li Jian (李健) to A$AP Ferg and Little Simz.

But constantly changing regulations can leave even the most seasoned industry leaders like Scorched puzzled as they wrestle with frequent “inconsistencies between Chinese consulates, embassies, and visa centers.” For example, some insist upon original documentation while others allow scans. Chasing down original signatures through international post may seem like a small annoyance but can cause serious setbacks amidst unpredictable timelines and fast-changing rules.

In China, working with an experienced promoter is a must for navigating the unexpected. Success stories still outnumber failures and by working with the right partners, international acts such as Chromeo, The Jesus & Mary Chain, Masego, and Lil Yachty have all packed out rooms across China in the last six months.

Today, the government still regulates China’s lean information diet; its internet censorship is one of the most extensive and complex in the world. Putting together a compelling local strategy in China is as important as it is challenging since most Western social media platforms and search engines are blocked in China. While many young people use virtual private networks (VPNs) to sidestep the government’s internet censorship, music distribution and promotion still happen predominantly on local platforms.

charityssb of Shanghai collective Genome 6.66Mbp

Photo by Catherine Lee

August Cohlmia, founder of Shanghai-based booking agency and artist management consultancy Alchemist Asia, has met both a fair share of challenges and successes looking after acts such as Ryan Hemsworth, Sevdaliza, and BADBADNOTGOOD in China.

For Cohlmia, it’s not the visa approval process but marketing and promotion that pose the greatest challenges.

“Though the landscape has become much more open for audiences in China to discover and connect with new artists, there still exists many factors and styles of marketing unique to China that an artist or their manager are not familiar with and may not be comfortable with at first,” explains Cohlmia.

In other words, when in China, do as the Chinese do.

“While of course, it’s always the job of a booking agent to make sure an artist is represented according to their needs and how they want to be portrayed, we need to help them understand that China is still a very different market than what they’re used to. Participating in things like interviews with Chinese publications, streaming sessions, engaging with fans on Weibo (China’s equivalent of Twitter), collaborations with record labels, etc., can absolutely get an artist more attention ahead of their tours here and create a real conversation with a potentially huge fanbase.”

Arkham Shanghai

Photos by Marie Berger

Fortunately, most Western distributors and labels distribute directly to Chinese DSPs, but despite some similarities, these and other Chinese platforms differ too greatly to take the same approach as in the West.

For example, top streaming services QQ and Netease both have wildly popular built-in social timelines similar to a Facebook feed with commenting, sharing, and liking functions. High engagement on these timelines can vastly improve a track’s performance and spread its reach exactly where streams and discovery happen. Fan engagement on Chinese DSPs is even more powerful than platform-controlled playlists or banner features — one could even argue that music discovery in China is, ironically, more democratic than in the West.

Main China Social Media: WeChat, Weibo, TikTok

Main China DSPs: QQ, Netease (网易), Kugou (酷狗), Kuwo (酷我), Xiami (虾米)

Blocked in China: Google, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube

That said, simply getting access to DSPs’ social features is an arduous process, especially for a non-Chinese speaker. This usually involves contacting the platform directly, binding the account to a local phone number, submitting passport scans, and navigating the backend entirely in Chinese. As a result, many artists miss out on building a local presence that is key for their future in China.

The bright side is that for more resourceful artists who do make their way onto local platforms, there is a sincere appreciation from fans (and being a big fish in a small sea of international artists activated on local platforms presents its own opportunities). In one instance, Adam Miltenberger, a resourceful manager who formerly worked with alt-R&B artist JMSN, put out a call for help on Instagram after announcing a run of China dates in 2017. Fortunately, an eager young fan responded and helped him gain access to DSP’s timelines and navigate Weibo, which greatly helped to promote their tour.

Artist Kristen Ng

Photo by Colin 四四

While at first glance, touring China may seem more trouble than it’s worth, there is a silver lining: a massive fanbase behind the firewall who simply can’t take their favorite international artists for granted.

On the industry side, passionate people behind the scenes keep things afloat, such as Kristen Ng, a Chengdu-based artist who goes by KAISHANDAO. As the founder of Chengdu culture blog Kiwese and an independent music promoter for NU Space, Ng sees such challenges as “just one side of the coin, one that is ignored or unknown to the vast majority of music punters.” Despite all the obstacles, the demand and support for independent music and culture events are growing as the underground scene continues to thrive in new and innovative ways.

When asked what keeps her going despite the newfound red tape, Ng’s answer is refreshingly optimistic.

“The spirit of change. The pooling together of can-do attitudes. The excitement and activity. The ups and downs. The push and pull. While certainly challenging, it’s never boring. This weekend alone [in Chengdu] there was a three-day outdoor ambient music festival, an experimental East Asian music collective, the reopening of an underground club with a headline from Ostgut Ton, and a return DJ set from techno producer Marco Shuttle. Not to mention parties of all genres scattered throughout the week, a BBQ at a tattoo studio, a live modular show, and everything in between. It’s non-stop and a thrill to be part of.”

There is an unspoken assumption within the Western music industry that modernization means Westernization. But a quick look at China’s past and present makes it clear that this may never be the case for the Middle Kingdom. In fact, China has become a key market, highly rewarding to those willing to put in the extra elbow grease to crack it.

Photo by Thanakrit Gu

Allyson Toy is a US/China-based music and media professional with over 12 years of experience in artist management, music touring, original content creation, marketing, and talent programming in both East and West. Toy has previously handled artist relations for Red Bull, 88rising and The FADER and worked in music touring at WME and CAA. She is passionate about helping friends and artists better understand China, DJing, discussing Asian American issues and overeating.

Interested in writing for Level? ↳